The Pyramid of Purpose

Every individual action in a company should be anchored on the company’s purpose. Skip this exercise at the cost of employee alienation, micromanagement, and general unhappiness.

Have you ever felt lost at work, without a clear understanding of the purpose of your current tasks, and without a clear picture of where your company was headed? I’ve yet to meet someone who would answer no to this question. If that’s your case, please reach out and let me know how I can apply to your company!

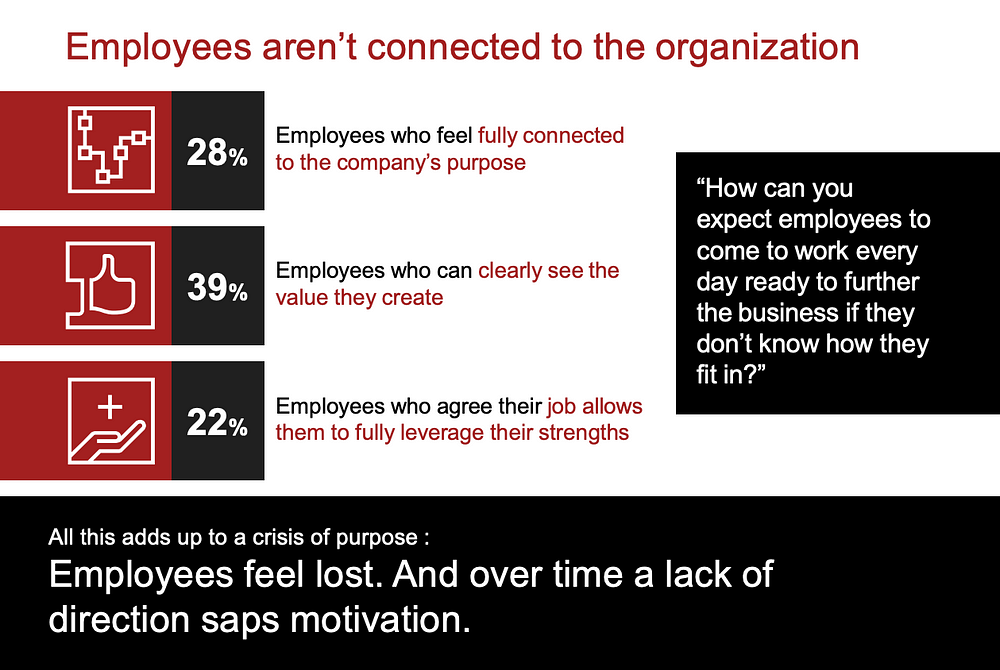

The evidence is not anecdotal either. A recent study by PWC Strategy& showed that, across 540 participants, only 28% claimed to feel fully connected to the company’s purpose, while less than half could clearly see the value they created.

Disengagement is usually due to a lack of anchoring: your company’s overall goal might be unclear to you, or you might not understand how your current work contributes to it. On the other hand, management that fails to make goals clear — and therefore engage their workforce — will often feel like work isn’t proceeding as they would like it to, or on the tasks that matter. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle of frustration rarely seen outside of the men’s rights movement.

Making it crystal clear to everyone how their work aligns with the company’s objectives is one of the most essential pieces of work that a company’s leadership can do. However, beyond maybe business objectives, few companies dedicate sufficient effort to clearly defining the foundations of their employees' work.

Those foundations are critical: there is a full Pyramid of Purpose behind any individual task. I’m going to break them out here.

The layers of the pyramid

I’ve mentioned before that product management isn’t about features. Features don’t exist in a vacuum and cannot be assessed in one: they are just a means to an end, the end being a business objective. But business objectives themselves are in service of the strategy. So, let’s get back to the basics and unpack the layers of the pyramid, one by one. They are, starting with the most foundational:

- Values: what drives you; what you want your organization to embody

- Vision: what your company — and the world — will look like once you have succeeded

- Mission: what products you will build, and for whom

- Goals: the milestones on the way to success

- Strategy: your approach to reaching these goals

- Business objectives: individual, measurable indicators that you will need to move to succeed in your strategy

- Features: and other individual pieces of work that you will need to deliver to affect business objectives

One note before we continue: you will see this pyramid represented elsewhere, more or less similar to what you’ll see here. Is my version the final one that will put this debate to rest? Why, yes, it is¹! Regardless, if a different representation works better for you, that’s fine, and my overall point on the grounding of individual actions in a global purpose will remain valid. But here’s how I think about those layers.

Values

Values are not just abstract principles that guide an organization’s decisions. They are deeply personal, reflecting what drives you as a founder or a leader. They are the bedrock upon which everything else in your business is built, and they should resonate with you on a personal level, not just be a set of rules your company follows.

What excites you? Is it the potential for financial success? The opportunity to make a difference in your community? The challenge of solving complex problems? These are the factors that, whether you realize it or not, shape your decision-making and steer you toward your goals.

The values are sometimes seen as less than critical, since they may seem to be relatively detached from how the business runs. “Sure”, one may think, “We’ll write somewhere that we won’t do evil, and so on, and we’ll be done with the values.” That’s not the right way to look at them, and you would be wrong to assume values are detached from day-to-day operations.

In The Undoing Project, Michael Lewis quotes psychologist Amos Tversky as saying²:

“The big choices we make are practically random. The small choices probably tell us more about who we are. Which field we go into may depend on which high school teacher we happen to meet. Who we marry may depend on who happens to be around at the right time of life. On the other hand, the small decisions are very systematic. That I became a psychologist is probably not very revealing. What kind of psychologist I am may reflect deep traits.”

The same applies to companies. You may decide to start an AI company today, while you would have started a social network ten years ago: that much is down to market landscape, opportunity, or plain whim. But what kind of social network or AI company you will build will be decided by who you are and what captivates you.

Ingvar Kamprad, the founder and long-time head of IKEA, drove an old Volvo and lived in a very modest house. Those weren’t mere quirks of his personality: these are IKEA’s values incarnate. By living a life of thriftiness, Kamprad was able to instill this value throughout his organization. Ask yourself: would IKEA’s staff have been equally motivated to provide affordable furniture to the masses had their leader been showing up in a Lamborghini? Or think about Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, two characters in the same industry but whose values were diametrically opposite. The products they created were a reflection of those: Steve Jobs couldn’t have built Excel any more than Bill Gates could have conjured the iMac.

Values are also held for the longest timeframe: at least years, if not decades. Boeing has been having a hard time lately, with numerous incidents indicating declining quality, whereas the company was once the gold standard for flight safety. Most commentators identified their 1997 merger with McDonnell Douglas as the ultimate cause for this change in culture. If this is correct, it would mean that it took almost 30 years for this change in values to be effective³.

Vision

A vision is, simply put, the picture of your company and the world around it when you have reached your objectives. Close your eyes and look at yourself in five or ten years: what do you see? That picture is the vision. Visions are critical but too often way too generic to be helpful (“We want to be the best in XYZ”), and I’ve written in the past about how to make sure yours is up to its task.

The vision includes both what the world will look like in the future you’re imagining, and what your company will be at that point. Famous visions abound. Kodak wanted to make photography “as convenient as a pencil” in a time when taking a picture involved large devices, dangerous chemicals, and specialized skills. Apple saw a future where everyone had a computer on their desk. Google aimed “to provide access to the world’s information in one click.”

Those were visions of companies that ended up succeeding, so it’s all too easy to see them as obvious in hindsight, but that would be a great mistake: at the time these visions were formulated, they were bold bets on the future, that could have paid off or not. By being able to entertain them, the leaders of those companies were able to work toward serving this future. In other words: they were skating where the puck was going to be — or at least where they thought it would. But the fact that your vision may end up being wrong shouldn’t stop you from pursuing it.

You might figure out that your vision is wrong, and need to pivot, but that should be an exception. Outside of cases of hard pivots, a vision should remain relatively unchanged for periods measured in years.

Mission

The mission is much more tangible while remaining fundamental: it is the definition of what you will do, for whom, and why you need to exist as an organization. It is the “How” to the company’s “Why” if you insist on thinking in these terms. Ford’s vision made it eschew the hand-made vehicles common at the time and focus on mass-produced cars as a way to build a future where every human was motorized.

This is also the layer where we can see critical differences between companies that may share a very similar vision, but based on different values. Apple and Microsoft come to mind once more: both companies worked towards a future where every person would have a computer, but their values were very different: while Apple focused on design and ease of use, Microsoft favored ubiquity and flexibility, leading ultimately to diametrically different missions — and very different companies.

Goals

These are tangible milestones on the long path to accomplishing something great.

When talking about goals at this level, we are talking about timeframes of years: it’s not about shipping some feature or other, but rather about the fundamental state of the organization. A goal for Microsoft was to have its operating system run a certain fraction of the world’s new computing power. Goals can be to reach certain fractions of the market, reach a certain price point for a given device, or whatever such large achievement that will show that your company is on the path to reaching its vision.

Strategy

While the goals are the targets you’re aiming for, the strategy describes how you intend to go from the status quo to reaching them. Lots of things will need to happen before you reach such milestones. Where will you start? Which of the numerous tasks in front of you is likely to yield benefits independently of its contribution to your vision? Which tasks are blocked, and which ones have synergies? What acquisitions or strategic partnerships may let you speed up your progress?

While the vision, mission, and values are all aspirational, the strategy is decidedly practical. “Strategy is a system of expedients,” in the words of Moltke. Finding and implementing it does not require dreamers but cunning operators. It is the bread and butter of people like Chief Operating Officers in companies or generals in armies: individuals who don’t decide on the long-term objective of their venture but find the best course of action to get there.

Business objectives

The business objectives may appear similar to goals, but they are much more down to earth. They should be measurable and expressed in numbers, and it should be possible to affect them within a timeframe of quarters. It is at this level that a company will decide that it needs to improve its conversion ratio, reduce its churn, or increase its sales in a certain geography.

“Ok, good, but why does that matter?”

As I’ve written before, features are just a means to an end. The same is true for any individual decision, taken anywhere in an organization: they are done to further the organization’s objectives. Without clarity on what a company intends to accomplish, it is impossible to assess which features should be prioritized, and staff will be left guessing at why what they toil over matters. This leads to confusion and alienation: lost and bewildered employees toiling at a drifting company.

On the other hand, having a clear purpose can make any piece of work truly meaningful. A custodian for the Apollo program once said, “I’m not mopping floors; I’m putting a man on the moon.”⁴ His work, which can seem menial, took a whole other dimension as it was firmly contextualized as a component of a grand vision.

And all levels of the pyramid are equally critical to firmly ground every day-to-day decision. I had consulted for a stock trading app in the past, where I had asked different product managers what they thought the focus of their company should be. The responses I got ranged from “a meme-stock casino” to a hands-off solution to build retirement savings. Both may be valid businesses, but there is not a single set of values nor a single vision that can encompass them: these answers were the clear sign of a rudderless company.

As a leader, it is your role to steer your company and provide your employees with direction. Doing so will improve everyone’s work by allowing them to anchor every decision, even the most menial one, as a necessary component to achieving a grand vision.

And while the individual words of the rungs of the Pyramid of Purpose are often bandied about, their meaning is often muddled, and few companies have any sort of clarity on what their values, vision, mission, etc., actually are. Don’t be one of them. Take this work seriously, clearly define where you are going, and you will be rewarded with a happier and more productive workforce.

¹ Narrator’s voice: it wasn’t meant to be

² Lewis, Michael. The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds, 2016.

³ This is as good a place as any to point out that, for values more than for any other layer of the pyramid, what a company says can be very different from what it does. For instance, one would be hard-pressed to find a company that doesn’t stress publicly that it is engaged in diversity, equality, and inclusion initiatives. However, the actual commitments vary heavily, in practice.

⁵ Helmut von Moltke, 1869 Instructions for Large Unit Commanders, translated by Daniel J. Hughes and published in Helmuth Karl Bernhard von Moltke, Daniel J. Hughes, and Harry Bell. Moltke on the Art of War: Selected Writings. Random House Publishing Group, 1993.

About me

I’m a product manager, 500 Startups alumnus, and consultant.

I’m head of product at a growth company and consult on product management in large companies and startups alike.

The rest of the time, I read random books and cook vast amounts of food.

Connect with me through my website, Medium, and LinkedIn.